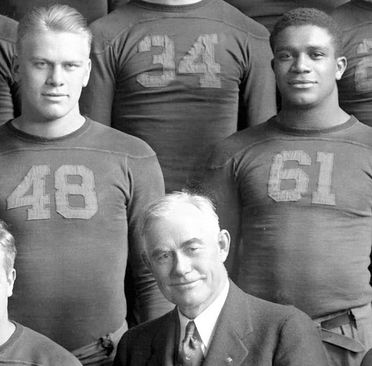

In 1932, Willis Ward became the first black football player to earn a varsity letter at the University of Michigan since George Jewett who played in 1890 & 1892. The legendary University of Michigan football coach, Fielding Yost, son of a confederate soldier had refused to recruit black athletes. However, the new coach, Harry Kipke, with the help of a very powerful group of alumni forced, then athletic director Yost, to accept Willis Ward. However, when Georgia Tech came to Michigan to play football in 1934, they threatened not to play the game if Willis Ward, played for Michigan.

A recent documentary titled “Black and Blue” retells and embellishes a story told of the heroism of President Gerald Ford in taking a stand to quit the team if Willis Ward was benched[1]. A large part of the role claimed for Gerald Ford was untrue and the story first became public in 1974 when Ford became Vice President and it was widely publicized during Ford’s presidential campaign in 1976 when he was having trouble with black voters because of his voting record on civil rights. The myth obscures the real heroism of the Michigan students, faculty and alumni who went to great lengths to protest the unfairness of Georgia Tech’s Jim Crow demands and the terribly difficult decision that Willis Ward had to make, which affected the rest of his life.

In his autobiography, Gerald Ford made only two claims[2];

· He wrote to his stepfather asking him if he should quit the football team in protest if Willis Ward was benched and that his stepfather advised him to do whatever the coaches wanted him to do.

· He was unsatisfied with that answer and so he went to Willis Ward who convinced him to play in the game.

Willis Ward contradicted the second part of that account in interviews in 1976 and 1983. He was asked directly if Gerald Ford had ever talked to him about not playing in the game and Ward said no.

Pollock interview 1983 (page 10)[3]:

· WARD: I know that Jerry and Bill Borgmann felt bad about it. And Jerry thought of quitting, I heard.

· POLLOCK: Did he discuss it with you at all?

· WARD: No, he didn't discuss it. He discussed it with the coach, and he discussed it with his stepfather. And he was hurt. I could tell. The attitude of the team. And we were a team, a unit, and we wound up with as bad a football season as Michigan ever had.

Ward was not telling the story from a contemporaneous memory but instead the first time he heard the story of Gerald Ford wanting to quit the team in protest was on a trip to Washington DC while Ward was serving on the Michigan Public Services Commission. He heard the story from one of Gerald Ford’s brothers. Ward served on the Commission from 1966 to 1972 and he was interviewed extensively by John Behee in 1970 for his book about black athletes at the University of Michigan[4]. In that interview, Ward talks extensively about the Georgia Tech game but never mentions the story about Gerald Ford[5]. Thus it is likely that Ford’s brother told Ward the story sometime between 1970 and 1972.

The narrator in the documentary dramatically tells how Gerald Ford walked into Coach Kipke’s office and said “I quit”. That is unlikely for several reasons; primary among them is the involvement of Michigamua, a University of Michigan senior honor society, in supporting Fielding Yost’s decision to bench Willis Ward. Gerald Ford joined Michigamua just a few weeks after the Georgia Tech game. The only source the producer could site for the dramatic story was that it was a “family story” and he thought perhaps Ford’s daughter, Susan Ford Bale, had told him the story.

Fielding Yost was a very important honorary member of Michigamua. The group took on the guise of a fictitious Indian tribe. His tribe name was “The Great Scalper”. Not only was he a legendary football coach but he had raised money to pay to remodel the groups clubhouse on the top floor of the Michigan Union and collected many Native American artifacts for the club to use in their ceremonies. The new clubhouse had opened in October 1933, one year before the Georgia Tech game.

Fielding Yost had asked his brother in-law Dan McGugin, the football coach at Vanderbilt, to arrange a game with a southern school. McGugin was good friends with the Georgia Tech coach and on November 11, 1933, Yost agreed with Georgia Tech to play in Ann Arbor the next fall. By January 3, 1934, the Georgia Tech athletic board wanted assurances that Michigan would not play any Negro athletes[6]. Yost did not immediately answer but by March[7] and April[8] the Georgia Tech letters became more insistent and suggested that it would be better to cancel the game then rather than later, but they must have received some assurances because the game was not canceled. Though he would never admit it publicly, Yost was obviously the decision maker with regard to the benching of Ward.

Two days before the game, a group that called itself the Ward United Front Committee announced that they had more than 1,500 signatures on a petition to ask the Coach not to prevent Willis Ward from playing in the game[9]. They called for a meeting the next night in the Natural Sciences auditorium and invited coach Kipke and Yost to come hear their petition.

Yost heard rumors that the students were going to plan a “sit down strike” on the football field during the game. He was so concerned that some of the opponents of his decision would cause such an incident at the game that he hired a Pinkerton detective to interview the leaders of the opposition and attend the rally. He also sent the Michigamua Fighting Braves to disrupt the meeting.

The Michigan Daily wrote;

· A declaration of gratitude to those students, faculty and organizations that have aided in the campaign for his participation in the Georgia Tech game Saturday was made last night by Willis Ward.

· Meanwhile, plans were completed for the student rally to be held at 8 p.m. tonight in the Natural Sciences auditorium for the purpose of crystallizing sentiment on the Ward affair.

· In response to an invitation to present their views on the matter, Athletic Director Fielding H. Yost declined, but Head Coach Harry Kipke could not be reached at a late hour last night for a statement as to whether he will appear at the meeting.

The meeting was held on October 19, 1934 and the auditorium was packed to overflowing. The Michigan Daily wrote;

Hecklers turn meeting into tumultuous verbal controversy. Prof. McFarlan is unable to speak.

· Smoldering feelings on the question of Willis Ward’s participation the Georgia Tech game burst into flame last night at what was probably the wildest and strangest Friday night rally in Michigan’s history…the meeting …developed into a bitter verbal battle between student factions espousing each side of the question.

· Speaker followed speaker in rapid succession as leaders of each side braved the heckling of their opponents to talk on issues varying from interpretations of true Christianity to the degree of hospitality due to guests.

· The heckling began when Abner Morton, Grad., chairman of the meeting attempted to speak. He was met with boos, clapping and wisecracks and it took him fifteen minutes to introduce the first speaker Prof. Harold McFarlan of the Engineering College, Socialist congressional candidate from the district. Apparently unabashed by the professorial rank, the hecklers kept up their banter and booing with unrelenting vigor. Occasional coins were tossed at the speaker…Morton then challenged the group sitting on the right side of the auditorium, where the hecklers were centralized, to send one of their numbers to the platform. After taunts of “yellow” from the left side of the audience, one of the “right” faction came forward to speak. He declared that the sponsors of the Ward movement say “it would be un-Christian to discriminate against Ward” but don’t realize that it would be just that to permit him to play because in all likelihood he would be injured in the game. He further argued that the coaches who had improved Ward’s playing ability should have the right to say whether or not he should risk that ability.

· Harvey Smith, captain of the track team (authors note: he is a member of the tribe of 1935), stated that those who were demanding that Ward play did not know Ward. On the other hand Smith said, those who opposed his playing knew him best and were interested in his welfare. Smith said that he and Ward had roomed together when the track team had gone on trips last spring.

Laurence Smith of the tribe of 1935, when asked for any noteworthy activities of his tribe, wrote[10];

· Broke up a rally in the Natural Sciences auditorium over the fact that Willis Ward was not allowed to play in the Georgia Tech game because of his race. We broke up the protest rally by reading filibuster speeches supporting the coaches’ decision. It got pretty funny before it was over.

A letter to the Michigan Daily described it as follows;

· Much to my disillusionment, a hostile audience, interested in but one side of the question, and led by an arrogant, aristocratic fraternal group, refused to confine their opposition to the established mediums of logical refutation. Insisting on preventing opposing speakers from stating their convictions, this gang adopted Hitleristic tactics of shouting down any speaker who differed with their dogmatic pre-conceived notions”

Gerald Ford was not initiated into Michigamua in the spring like most of the members of the Tribe of 1935; rather he was the last initiate in the fall. It should also be kept in mind that Michigamua had never initiated a Negro member. Willis Ward was much more of a football star than was Ford and he was a very good student. Thus, if not for his race, he would have made a more attractive tribe member than Ford.

The Minutes of the Michigamua meetings show that Ford was voted in on 11/25/34 and initiated on 12/2/34. This was only 5 weeks after Michigamua had played such a crucial role in supporting the coaches’ decision not to play Ward. All votes for membership had to be unanimous, thus one “black ball” and Ford would not have been elected to membership. The captain of the football team, the football team manager and the student representative to the Board in Control of Athletics, were all members of Michigamua. Yost was such an important member of Michigamua that the tribe continued to visit his widow for tea every spring on his birthday, until her death. It seems highly unlikely that not one member of Michigamua would vote against the membership of someone who had opposed Yost’s decision in such a dramatic manner or that Gerald Ford would want to join such an organization that so opposed his own views on the Ward matter.

Ford was a lifelong member of the Michigamua alumni and he regularly came back to visit the members of the tribe. When the group was being pressured under Title IX to allow women to join the group, the Chief of the tribe wrote to, then President Ford, asking for him to talk to the University President on their behalf[11].

In addition, Ford was personally recruited by Coach Kipke and since Ford was not able to afford to go to the University of Michigan, Coach Kipke also found Ford a job waiting tables. Ford also went to Coach Kipke that spring to ask him for a job as an assistant coach so that he could support himself while he went to law school. Kipke could not hire him but he did help him find a job at Yale as an assistant football coach, where he eventually enrolled in the Law School. Would Coach Kipke have done that for someone who had quit the team?

There is no doubt that Ford was opposed to the coaches decision not to play Ward but it is unlikely that he told Coach Kipke that he would quit and he certainly took no public stand on the issue.

The producers of the documentary also included an interview of Gerald Ford on the Larry King show but they edited out a portion, saying that Ford had “misremembered something” and they did not want to embarrass him. What they edited out was the truth, which was that Ford, along with the rest of the team, were told that Willis Ward had gone to Coach Kipke and “volunteered” to sit out the game so as not to cause the University any embarrassment. President Ford also wrote the following in the New York Times on August 8, 1999[12];

· I was a University of Michigan senior, preparing with my Wolverine teammates for a football game against visiting Georgia Tech. Among the best players on that year's Michigan squad was Willis Ward, a close friend of mine whom the Southern school reputedly wanted dropped from our roster because he was black. My classmates were just as adamant that he should take the field. In the end, Willis decided on his own not to play.

How Willis Ward was convinced to volunteer is a story in itself.

Coach Kipke and Harry Bennett, protégé of Henry Ford, had an arrangement where star football players at the University would get summer, weekend & holiday jobs at the Ford Motor Company that would support them since at that time student athletes did not receive scholarships[13]. Reportedly, they spent some of their time at the Rouge River Plant playing practice football games. This employment arrangement was an apparent violation of conference rules.

Willis Ward tells the story that Henry Ford and his son, Edsel, were at a UM football game in the fall of 1932 and saw Ward play a particularly good game. Henry told Edsel that he wanted Ward to work at Ford Motor Company. Harry Bennett, who was Henry Ford’s right hand man, hired Willis Ward for the summer of 1933 and began grooming him for a career at Ford. The first summer he drove a truck making deliveries around the River Rouge Plant. Later he went to work in the black employment office with Don Marshall. After he graduated he was made an executive in charge of the black employment office.

When Ward began to ask Coach Kipke if he would play in the Georgia Tech game, Kipke told him that if he made a fuss, Kipke would never recruit another black player. As the situation broke in the newspapers, Ward was getting strong pressure from his friends and the black community as a whole, to quit the team if he was benched. The black churches in Detroit had taken up a collection to pay Ward’s college expenses if he quit the team. Kipke made a call to Harry Bennett asking for his help with Ward. Ward describes his meeting with Bennett as a meeting with a “Dutch uncle” (meaning that Bennett was twisting his arm). Bennett told him that he had a future at Ford Motor Company and that he needed to “remember who your friends are”. Thus, Willis Ward “volunteered” to sit out the game and he was later vilified in the black press for that decision.

Ward describes at length in each of his interviews, how that decision broke his spirit and effectively ended his athletic career and his Olympic aspirations in Track & Field. It set in motion a pattern in Willis Ward’s life where he would look to powerful white men for job opportunities and political appointments. His job at Ford Motor Company was filled with controversy in the black community.

Willis Ward’s Work at the Ford Motor Company[14]

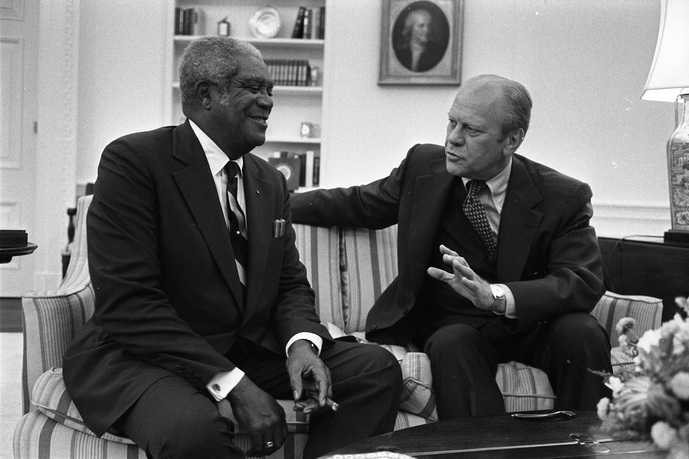

Willis Ward had long wanted to be appointed as a judge. In 1968, he wrote to then Governor, George Romney asking to be considered for one of two vacancies on the Wayne County Circuit Court[15]. Romney did not appoint him to the court. After he had spoken with President Ford’s brother, Ward again wrote to then Governor Milliken and this time was appointed to a vacancy in the probate court in December 1972[16].

The first time that Gerald Ford’s role in the Willis Ward incident appears in print was an article written on February 23, 1974, with the headline “Judge Ward Broke U-M Barriers” and published in the Michigan Chronicle, Detroit’s major black weekly newspaper[17]. The only reference to Gerald Ford’s role was a quote from Ward;

· One of Ward’s teammates was Vice President Gerald Ford, who wanted to quit after the Georgia Tech incident, in support of his friend. “He is basically a very decent man.” Ward observed. “I like Gerry”. (Ford became Vice President December 6, 1973)

The first appearance of Gerald Ford’s role in the white press was in an article written on August 22, 1974 by Fred Delano in The Observer & Eccentric, just 13 days after Gerald Ford was sworn in as President[18]. The headline read “The day Jerry Ford Almost Quit the Team”. The focus had shifted from Willis Ward to Gerald Ford. Fred Delano had been a sports reporter for the student newspaper, the Michigan Daily, in 1934. He quotes Ward as saying “I understand indirectly that Jerry called his father to talk over whether he should quit the team because of it”. Ward is retelling the story that he had been told by President Ford’s brother.

The article goes on the put the story in the context of Gerald Ford’s voting record on black issues;

· President Ford hardly draws hussahs from the black press for his voting record on civil rights issues during his career in Congress. That it “leaves much to be desired” is about the best the current edition of the Michigan Chronicle, Michigan’s foremost black weekly can say about that record.

· Judge Ward: “He’s a conservative. He had to be elected to Congress for 25 years in that Grand Rapids district. His voting record makes it appear-APPEAR-as not decent to the colored man, but Jerry may be like Lyndon Johnson as a president who lets his basic decency come through. It will disappoint and surprise me if it doesn’t come through. I’m optimistic. It’s there in Jerry and I have great hopes as to his civil rights attitudes.”

The story was much publicized during President Ford’s reelection campaign in 1976. On January 22, 1976 the AP wire service circulated a story about Ford’s role in the Georgia Tech/Willis Ward incident that was widely printed in newspapers around the country.

Willis Ward was interviewed for the campaign and his telling of the story became the centerpiece of a film that was shown at the Republican National Convention just before Gerald Ford’ acceptance speech. Ford’s campaign manager wrote to Willis Ward thanking him for his part in the film[19];

Fielding Yost was a very important honorary member of Michigamua. The group took on the guise of a fictitious Indian tribe. His tribe name was “The Great Scalper”. Not only was he a legendary football coach but he had raised money to pay to remodel the groups clubhouse on the top floor of the Michigan Union and collected many Native American artifacts for the club to use in their ceremonies. The new clubhouse had opened in October 1933, one year before the Georgia Tech game.

Fielding Yost had asked his brother in-law Dan McGugin, the football coach at Vanderbilt, to arrange a game with a southern school. McGugin was good friends with the Georgia Tech coach and on November 11, 1933, Yost agreed with Georgia Tech to play in Ann Arbor the next fall. By January 3, 1934, the Georgia Tech athletic board wanted assurances that Michigan would not play any Negro athletes[6]. Yost did not immediately answer but by March[7] and April[8] the Georgia Tech letters became more insistent and suggested that it would be better to cancel the game then rather than later, but they must have received some assurances because the game was not canceled. Though he would never admit it publicly, Yost was obviously the decision maker with regard to the benching of Ward.

Two days before the game, a group that called itself the Ward United Front Committee announced that they had more than 1,500 signatures on a petition to ask the Coach not to prevent Willis Ward from playing in the game[9]. They called for a meeting the next night in the Natural Sciences auditorium and invited coach Kipke and Yost to come hear their petition.

Yost heard rumors that the students were going to plan a “sit down strike” on the football field during the game. He was so concerned that some of the opponents of his decision would cause such an incident at the game that he hired a Pinkerton detective to interview the leaders of the opposition and attend the rally. He also sent the Michigamua Fighting Braves to disrupt the meeting.

The Michigan Daily wrote;

· A declaration of gratitude to those students, faculty and organizations that have aided in the campaign for his participation in the Georgia Tech game Saturday was made last night by Willis Ward.

· Meanwhile, plans were completed for the student rally to be held at 8 p.m. tonight in the Natural Sciences auditorium for the purpose of crystallizing sentiment on the Ward affair.

· In response to an invitation to present their views on the matter, Athletic Director Fielding H. Yost declined, but Head Coach Harry Kipke could not be reached at a late hour last night for a statement as to whether he will appear at the meeting.

The meeting was held on October 19, 1934 and the auditorium was packed to overflowing. The Michigan Daily wrote;

Hecklers turn meeting into tumultuous verbal controversy. Prof. McFarlan is unable to speak.

· Smoldering feelings on the question of Willis Ward’s participation the Georgia Tech game burst into flame last night at what was probably the wildest and strangest Friday night rally in Michigan’s history…the meeting …developed into a bitter verbal battle between student factions espousing each side of the question.

· Speaker followed speaker in rapid succession as leaders of each side braved the heckling of their opponents to talk on issues varying from interpretations of true Christianity to the degree of hospitality due to guests.

· The heckling began when Abner Morton, Grad., chairman of the meeting attempted to speak. He was met with boos, clapping and wisecracks and it took him fifteen minutes to introduce the first speaker Prof. Harold McFarlan of the Engineering College, Socialist congressional candidate from the district. Apparently unabashed by the professorial rank, the hecklers kept up their banter and booing with unrelenting vigor. Occasional coins were tossed at the speaker…Morton then challenged the group sitting on the right side of the auditorium, where the hecklers were centralized, to send one of their numbers to the platform. After taunts of “yellow” from the left side of the audience, one of the “right” faction came forward to speak. He declared that the sponsors of the Ward movement say “it would be un-Christian to discriminate against Ward” but don’t realize that it would be just that to permit him to play because in all likelihood he would be injured in the game. He further argued that the coaches who had improved Ward’s playing ability should have the right to say whether or not he should risk that ability.

· Harvey Smith, captain of the track team (authors note: he is a member of the tribe of 1935), stated that those who were demanding that Ward play did not know Ward. On the other hand Smith said, those who opposed his playing knew him best and were interested in his welfare. Smith said that he and Ward had roomed together when the track team had gone on trips last spring.

Laurence Smith of the tribe of 1935, when asked for any noteworthy activities of his tribe, wrote[10];

· Broke up a rally in the Natural Sciences auditorium over the fact that Willis Ward was not allowed to play in the Georgia Tech game because of his race. We broke up the protest rally by reading filibuster speeches supporting the coaches’ decision. It got pretty funny before it was over.

A letter to the Michigan Daily described it as follows;

· Much to my disillusionment, a hostile audience, interested in but one side of the question, and led by an arrogant, aristocratic fraternal group, refused to confine their opposition to the established mediums of logical refutation. Insisting on preventing opposing speakers from stating their convictions, this gang adopted Hitleristic tactics of shouting down any speaker who differed with their dogmatic pre-conceived notions”

Gerald Ford was not initiated into Michigamua in the spring like most of the members of the Tribe of 1935; rather he was the last initiate in the fall. It should also be kept in mind that Michigamua had never initiated a Negro member. Willis Ward was much more of a football star than was Ford and he was a very good student. Thus, if not for his race, he would have made a more attractive tribe member than Ford.

The Minutes of the Michigamua meetings show that Ford was voted in on 11/25/34 and initiated on 12/2/34. This was only 5 weeks after Michigamua had played such a crucial role in supporting the coaches’ decision not to play Ward. All votes for membership had to be unanimous, thus one “black ball” and Ford would not have been elected to membership. The captain of the football team, the football team manager and the student representative to the Board in Control of Athletics, were all members of Michigamua. Yost was such an important member of Michigamua that the tribe continued to visit his widow for tea every spring on his birthday, until her death. It seems highly unlikely that not one member of Michigamua would vote against the membership of someone who had opposed Yost’s decision in such a dramatic manner or that Gerald Ford would want to join such an organization that so opposed his own views on the Ward matter.

Ford was a lifelong member of the Michigamua alumni and he regularly came back to visit the members of the tribe. When the group was being pressured under Title IX to allow women to join the group, the Chief of the tribe wrote to, then President Ford, asking for him to talk to the University President on their behalf[11].

In addition, Ford was personally recruited by Coach Kipke and since Ford was not able to afford to go to the University of Michigan, Coach Kipke also found Ford a job waiting tables. Ford also went to Coach Kipke that spring to ask him for a job as an assistant coach so that he could support himself while he went to law school. Kipke could not hire him but he did help him find a job at Yale as an assistant football coach, where he eventually enrolled in the Law School. Would Coach Kipke have done that for someone who had quit the team?

There is no doubt that Ford was opposed to the coaches decision not to play Ward but it is unlikely that he told Coach Kipke that he would quit and he certainly took no public stand on the issue.

The producers of the documentary also included an interview of Gerald Ford on the Larry King show but they edited out a portion, saying that Ford had “misremembered something” and they did not want to embarrass him. What they edited out was the truth, which was that Ford, along with the rest of the team, were told that Willis Ward had gone to Coach Kipke and “volunteered” to sit out the game so as not to cause the University any embarrassment. President Ford also wrote the following in the New York Times on August 8, 1999[12];

· I was a University of Michigan senior, preparing with my Wolverine teammates for a football game against visiting Georgia Tech. Among the best players on that year's Michigan squad was Willis Ward, a close friend of mine whom the Southern school reputedly wanted dropped from our roster because he was black. My classmates were just as adamant that he should take the field. In the end, Willis decided on his own not to play.

How Willis Ward was convinced to volunteer is a story in itself.

Coach Kipke and Harry Bennett, protégé of Henry Ford, had an arrangement where star football players at the University would get summer, weekend & holiday jobs at the Ford Motor Company that would support them since at that time student athletes did not receive scholarships[13]. Reportedly, they spent some of their time at the Rouge River Plant playing practice football games. This employment arrangement was an apparent violation of conference rules.

Willis Ward tells the story that Henry Ford and his son, Edsel, were at a UM football game in the fall of 1932 and saw Ward play a particularly good game. Henry told Edsel that he wanted Ward to work at Ford Motor Company. Harry Bennett, who was Henry Ford’s right hand man, hired Willis Ward for the summer of 1933 and began grooming him for a career at Ford. The first summer he drove a truck making deliveries around the River Rouge Plant. Later he went to work in the black employment office with Don Marshall. After he graduated he was made an executive in charge of the black employment office.

When Ward began to ask Coach Kipke if he would play in the Georgia Tech game, Kipke told him that if he made a fuss, Kipke would never recruit another black player. As the situation broke in the newspapers, Ward was getting strong pressure from his friends and the black community as a whole, to quit the team if he was benched. The black churches in Detroit had taken up a collection to pay Ward’s college expenses if he quit the team. Kipke made a call to Harry Bennett asking for his help with Ward. Ward describes his meeting with Bennett as a meeting with a “Dutch uncle” (meaning that Bennett was twisting his arm). Bennett told him that he had a future at Ford Motor Company and that he needed to “remember who your friends are”. Thus, Willis Ward “volunteered” to sit out the game and he was later vilified in the black press for that decision.

Ward describes at length in each of his interviews, how that decision broke his spirit and effectively ended his athletic career and his Olympic aspirations in Track & Field. It set in motion a pattern in Willis Ward’s life where he would look to powerful white men for job opportunities and political appointments. His job at Ford Motor Company was filled with controversy in the black community.

Willis Ward’s Work at the Ford Motor Company[14]

Willis Ward had long wanted to be appointed as a judge. In 1968, he wrote to then Governor, George Romney asking to be considered for one of two vacancies on the Wayne County Circuit Court[15]. Romney did not appoint him to the court. After he had spoken with President Ford’s brother, Ward again wrote to then Governor Milliken and this time was appointed to a vacancy in the probate court in December 1972[16].

The first time that Gerald Ford’s role in the Willis Ward incident appears in print was an article written on February 23, 1974, with the headline “Judge Ward Broke U-M Barriers” and published in the Michigan Chronicle, Detroit’s major black weekly newspaper[17]. The only reference to Gerald Ford’s role was a quote from Ward;

· One of Ward’s teammates was Vice President Gerald Ford, who wanted to quit after the Georgia Tech incident, in support of his friend. “He is basically a very decent man.” Ward observed. “I like Gerry”. (Ford became Vice President December 6, 1973)

The first appearance of Gerald Ford’s role in the white press was in an article written on August 22, 1974 by Fred Delano in The Observer & Eccentric, just 13 days after Gerald Ford was sworn in as President[18]. The headline read “The day Jerry Ford Almost Quit the Team”. The focus had shifted from Willis Ward to Gerald Ford. Fred Delano had been a sports reporter for the student newspaper, the Michigan Daily, in 1934. He quotes Ward as saying “I understand indirectly that Jerry called his father to talk over whether he should quit the team because of it”. Ward is retelling the story that he had been told by President Ford’s brother.

The article goes on the put the story in the context of Gerald Ford’s voting record on black issues;

· President Ford hardly draws hussahs from the black press for his voting record on civil rights issues during his career in Congress. That it “leaves much to be desired” is about the best the current edition of the Michigan Chronicle, Michigan’s foremost black weekly can say about that record.

· Judge Ward: “He’s a conservative. He had to be elected to Congress for 25 years in that Grand Rapids district. His voting record makes it appear-APPEAR-as not decent to the colored man, but Jerry may be like Lyndon Johnson as a president who lets his basic decency come through. It will disappoint and surprise me if it doesn’t come through. I’m optimistic. It’s there in Jerry and I have great hopes as to his civil rights attitudes.”

The story was much publicized during President Ford’s reelection campaign in 1976. On January 22, 1976 the AP wire service circulated a story about Ford’s role in the Georgia Tech/Willis Ward incident that was widely printed in newspapers around the country.

Willis Ward was interviewed for the campaign and his telling of the story became the centerpiece of a film that was shown at the Republican National Convention just before Gerald Ford’ acceptance speech. Ford’s campaign manager wrote to Willis Ward thanking him for his part in the film[19];

· The Convention film that preceded the President’s acceptance speech on Thursday night has been universally praised by everyone from the President on down in the White House. It goes without saying one of the principle reasons for these accolades can be traced directly to your contribution to the film itself. We don’t believe the film had a more moving or emotional sequence than the one you provided in your discussion of the President’s football days and friendships at the University of Michigan.

By telling the story to Willis Ward and having him retell the story as if it were his own, it gave the story more credibility than if the story were told by President Ford or a family member.

As shown in the trailer for the documentary, the story became part of the eulogy given by President George W. Bush at President Ford’s funeral. The story has become integral to Gerald Ford’s identity.

The University of Michigan has become much invested in the story of Gerald Ford’s role in the Willis Ward / Georgia Tech football game story. In January 2013, The Gerald Ford School of Public Policy put on a screening of the documentary and a special panel discussion of the documentary[20]. The documentary was also aired on local television and producers said that they aired it because it was endorsed by the University. The documentary has also been played in K-12 schools throughout the state of Michigan. October 20, 2012 was celebrated at a UM football game as Willis Ward Day[21].

A story told by President Ford’s brother to Willis Ward about a private letter or phone call between Gerald Ford and his stepfather has grown into a dramatic scene of a confrontation with Coach Kipke and the famous words “I quit” and only Willis Ward himself could convince young Gerald Ford to play in the game. Unfortunately, none of the story can be corroborated by contemporaneous reports or by documents and the motive for embellishing or making up such a story to bolster an election campaign is obvious. The circumstantial evidence at the time indicates that it is unlikely that young Jerry Ford would have become known for fighting the coaches’ decision.

Thus, I must conclude that this story is more myth than reality. It should be relegated to the same place in history as the story about George Washington chopping down the cherry tree.

Attributions for the following exhibits:

Bentley Historical Library, UM Ann Arbor 6,7,8,9,10

Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library, Detroit 15,16,17,18

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Ann Arbor 3,11,19

Benson Ford Research Center, Dearborn 13

Video clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OPnufgMDr_k

Bentley Historical Library, UM Ann Arbor 6,7,8,9,10

Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library, Detroit 15,16,17,18

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Ann Arbor 3,11,19

Benson Ford Research Center, Dearborn 13

Video clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OPnufgMDr_k

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VAxx5UzKqPA

[2] A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford, Published August 1, 1979 by Harper & Row / Reader's Digest

[2] A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford, Published August 1, 1979 by Harper & Row / Reader's Digest

| 03_1983_pollock_interview_of_willis_ward_transcript.pdf |

[4] Hail to the victors! By John Behee, Ann Arbor, Mich.: distributed by Ulrich's Books, [1974]

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Rp9UfldWXY&feature=em-upload_owner

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Rp9UfldWXY&feature=em-upload_owner

| 06_letter_from_georgia_tech_coach_re_negro_players_jan_3.jpg |

| 07_letter_from_georgia_tech_coach_re_negro_players_march_17.jpg |

| 08_letter_from_georgia_tech_coach_re_negro_players_april.jpg |

| 09_willis_ward_petition_with_signatures.jpg |

| 10_michigamua_history_questionaire_larry_smith_re_willis_ward_meeting.jpg |

| 11_letter_to_president_ford_re_title_ix.jpg |

[12] http://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/speeches/990808.asp

[13] Willis Ward Oral History, Benson Ford Research Center

[13] Willis Ward Oral History, Benson Ford Research Center

| 14_willis_wards_work_at_the_ford_motor_company.docx |

| 15_letter_to_governor_romney_asking_to_be_appointed_judge_burton_library.jpg |

| 16_letter_from_governor_milliken_appointing_willis_ward_as_judge_burton_library.jpg |

| 17_michigan_chronicle_article_on_willis_ward_burton_library.jpg |

| 18_the_day_gerald_ford_almost_quit_the_football_team.jpg |

| 19_letter_to_ward_from_president_fords_office_thanking_him_for_his_interview.jpg |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed